Understanding the Stages of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer remains the most common cancer among women worldwide, accounting for over 2.3 million new cases annually, according to the World Health Organization. The breast, composed of glandular, fatty, and connective tissues, is especially susceptible to malignant transformation. Despite advancements in screening and treatment, late detection continues to hamper effective management and survival rates. Early recognition of the disease’s stages is crucial, as it directly impacts prognosis and therapeutic outcomes. Raising awareness about the progression of breast cancer is essential for timely intervention and improved patient care.

1. What Are Cancer Stages?

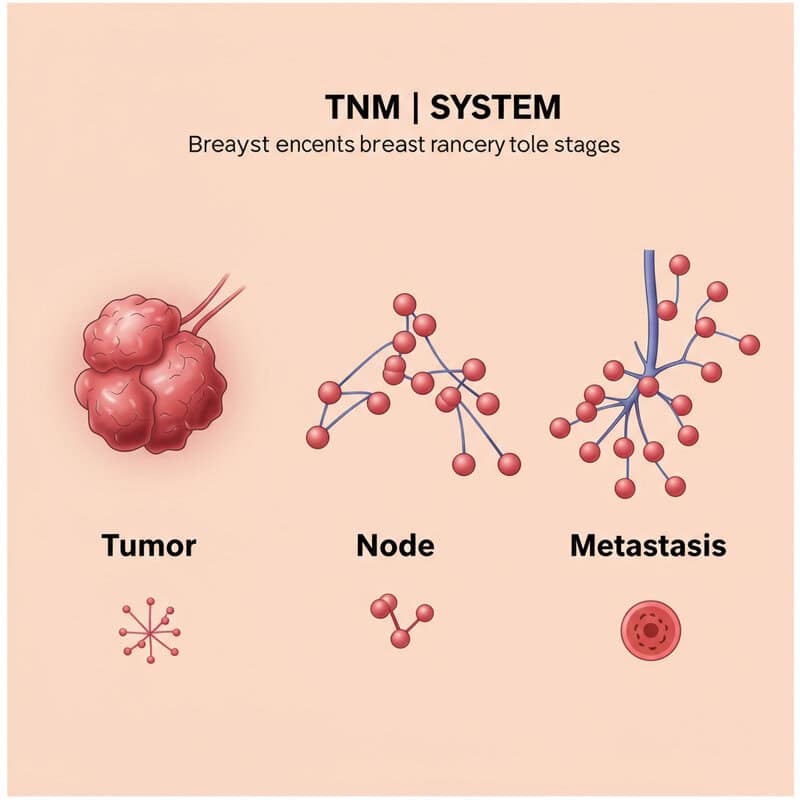

The concept of “staging” in cancer refers to the systematic process of determining how far a cancer has spread within the body at the time of diagnosis. Staging provides a common language for doctors to describe the extent and severity of cancer, which is critical for developing the most effective treatment plans and predicting patient outcomes. The main factors assessed during staging include the size of the primary tumor, involvement of nearby lymph nodes, and the presence of metastasis, or spread to distant organs.

Staging helps healthcare professionals tailor therapies—such as surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or targeted treatments—based on the specific characteristics of a patient’s cancer. Additionally, it allows for more accurate prognoses and helps guide discussions about survival rates and potential outcomes. Staging systems, such as the widely used TNM system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (American Cancer Society), are continually refined as research advances. Understanding cancer staging is essential for both clinicians and patients, enabling informed decision-making and improved communication throughout the cancer care journey.

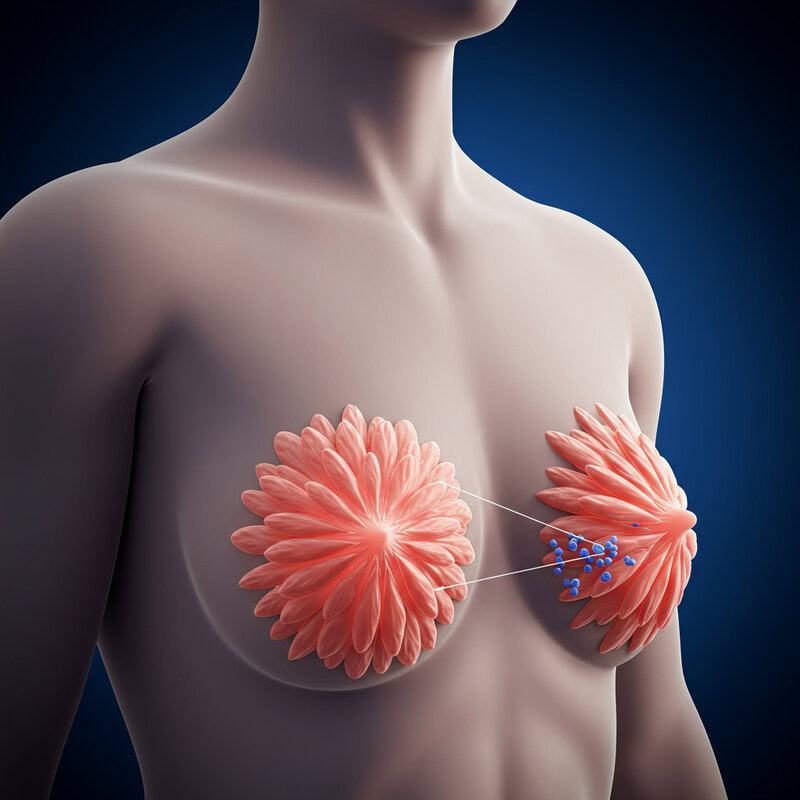

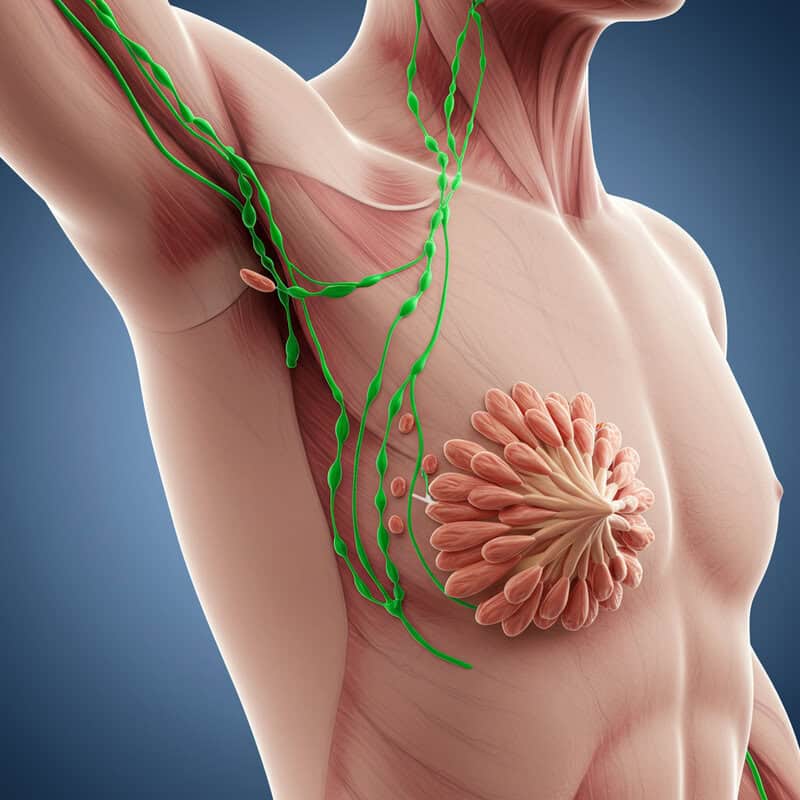

2. Breast Anatomy Basics

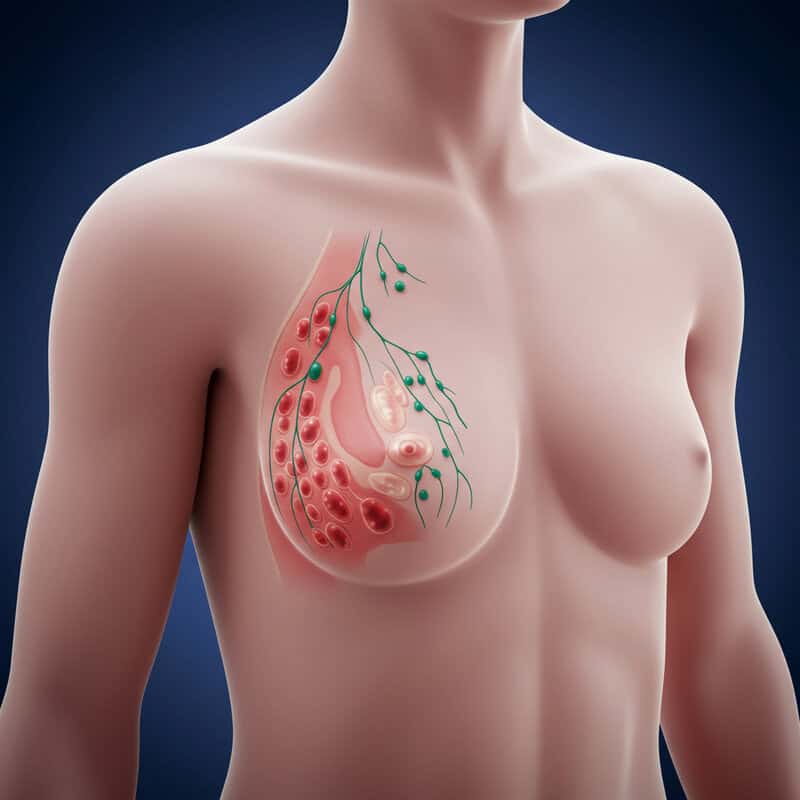

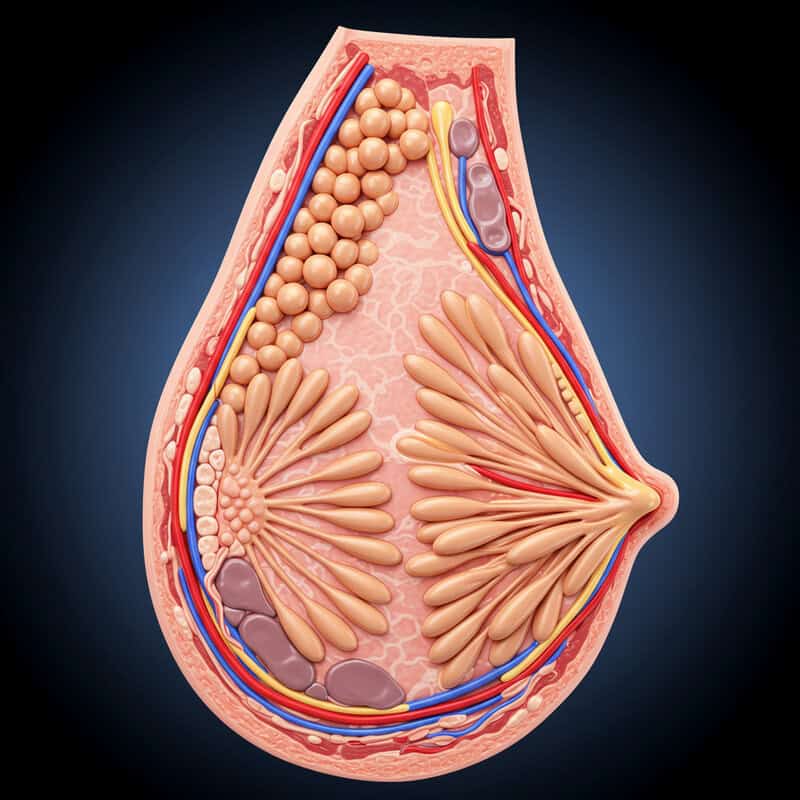

The breast is a complex organ primarily composed of glandular tissue, fatty tissue, and connective tissue. The glandular tissue includes lobules, which are small sacs responsible for producing milk, and ducts, thin tubes that carry milk from the lobules to the nipple. Fatty tissue surrounds and supports these structures, contributing to the size and shape of the breast. Connective tissue provides structural integrity and separates the different components within the breast.

Lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels are especially significant in understanding breast cancer, as they serve as pathways for cancer cells to spread beyond the original tumor. The most important lymph nodes in breast cancer are the axillary lymph nodes, located under the arm, but others include the supraclavicular (above the collarbone) and internal mammary nodes (inside the chest near the breastbone). When breast cancer spreads, it often first moves to these nearby lymph nodes before reaching distant organs. Understanding this anatomy is crucial for evaluating cancer stage and determining treatment strategies. For further details, visit the Breastcancer.org Anatomy Guide.

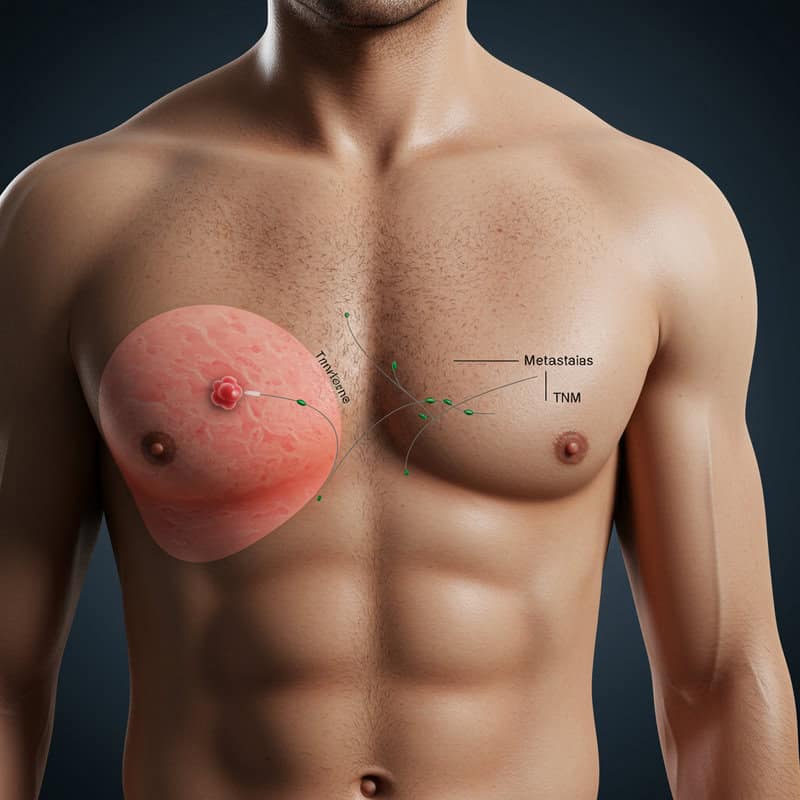

3. The TNM System

The Tumor, Node, Metastasis (TNM) system is the most widely used classification method for staging breast cancer worldwide. Developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the Union for International Cancer Control, the TNM system provides a standardized framework for describing the extent of cancer in the body. Each component of the system focuses on a specific aspect of cancer progression:

T (Tumor): Describes the size of the primary tumor and whether it has invaded nearby tissue.

N (Node): Indicates whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes and, if so, how many and how extensively.

M (Metastasis): Refers to the presence or absence of distant metastasis, meaning whether cancer cells have traveled to other organs or parts of the body.

By combining these categories, clinicians can assign an overall stage to the cancer, guiding treatment decisions and providing insight into prognosis. The TNM system is regularly updated to reflect new research and clinical findings, ensuring its relevance in contemporary cancer care. For more information, refer to the National Cancer Institute’s guide to cancer staging.

4. Stage 0: Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS)

Stage 0 breast cancer, also known as Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS), represents the earliest form of breast cancer. In this stage, abnormal cells are found exclusively within the lining of a breast duct and have not invaded surrounding breast tissue or spread beyond the ducts. DCIS is considered a non-invasive or pre-invasive cancer, as the malignant cells remain “in situ,” meaning “in place.”

Although DCIS itself is not life-threatening, it is a marker for an increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer in the future. Timely detection and treatment of DCIS are essential to prevent potential progression. Treatment options may include surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy), radiation therapy, and, in some cases, hormone therapy to reduce recurrence risk.

Since DCIS does not spread to lymph nodes or distant organs, its prognosis is generally excellent. However, careful monitoring and follow-up are critical for optimal outcomes. For more in-depth information about Stage 0 breast cancer and treatment approaches, visit the American Cancer Society’s page on breast cancer stages.

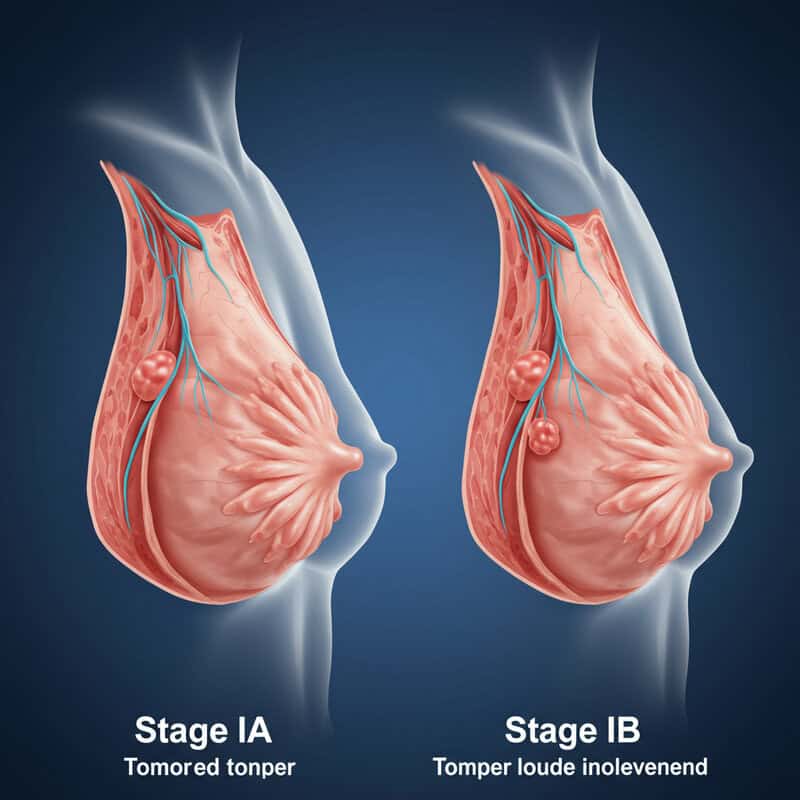

5. Stage I: Early Invasive Cancer

Stage I breast cancer marks the beginning of invasive disease, meaning cancer cells have spread beyond the ducts or lobules into the surrounding breast tissue but remain relatively localized. Stage I is subdivided into Stage IA and Stage IB:

Stage IA: The tumor is 2 centimeters or smaller and has not spread to lymph nodes.

Stage IB: There may be small clusters of cancer cells (no larger than 2 millimeters) in the lymph nodes, and the primary tumor is either not detectable or 2 centimeters or smaller.

Early detection at Stage I offers an excellent prognosis, with high survival rates and a variety of effective treatment options, including surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy), radiation, and possibly hormone or targeted therapies. The risk of recurrence or spread is relatively low, but ongoing monitoring and follow-up are vital. Personalized treatment planning is based on tumor characteristics, such as hormone receptor status and HER2 status, which help guide therapy decisions. For further details on Stage I breast cancer, visit the Breastcancer.org Stage I Overview.

6. Stage IA vs. IB

Stage I breast cancer is divided into two subcategories—IA and IB—based on the size of the tumor and the extent of lymph node involvement. Understanding these differences is essential for accurate prognosis and treatment planning.

Stage IA: In this subcategory, the tumor measures 2 centimeters or less in greatest dimension and has not spread to any lymph nodes. The absence of lymph node involvement generally indicates a lower risk of recurrence and a more favorable prognosis. Treatment often involves surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy) and, depending on other tumor characteristics, may include radiation or hormone therapy.

Stage IB: This subcategory is defined by either the presence of very small clusters of cancer cells (greater than 0.2 millimeters but not larger than 2 millimeters) in the lymph nodes, with no tumor in the breast, or a tumor 2 centimeters or smaller along with small clusters of cancer cells in the lymph nodes. The minimal lymph node involvement in Stage IB suggests a slightly higher risk compared to IA, but outcomes remain highly favorable. Treatments may be similar, but additional therapies are sometimes recommended based on individual risk factors.

For a detailed breakdown, visit the National Cancer Institute’s breast cancer staging guide.

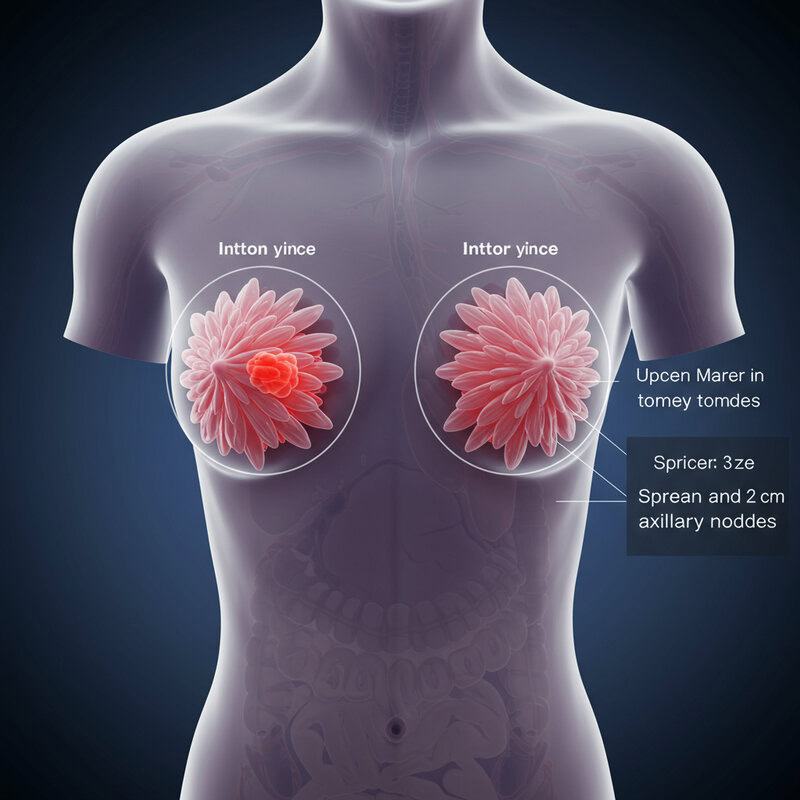

7. Stage II: Localized Spread

Stage II breast cancer represents a progression from early-stage disease, characterized by either larger tumor size, limited spread to nearby lymph nodes, or both. This stage is divided into IIA and IIB, each with specific criteria based on tumor dimensions and nodal involvement.

Stage IIA: This stage includes tumors up to 2 centimeters in size that have spread to 1-3 axillary (underarm) lymph nodes, or tumors between 2 and 5 centimeters that have not reached the lymph nodes. The combination of tumor size and early lymph node involvement signals a more significant risk than Stage I but is still considered highly treatable.

Stage IIB: Tumors in this subcategory are either between 2 and 5 centimeters with spread to 1-3 axillary lymph nodes, or larger than 5 centimeters without any lymph node spread. The increased tumor size and limited nodal involvement indicate a greater risk of further progression and recurrence.

Stage II breast cancer remains localized, meaning it has not spread to distant organs. Treatment typically involves a combination of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and possibly targeted therapies, tailored to individual tumor biology. For more information, refer to the American Cancer Society’s guide to breast cancer stages.

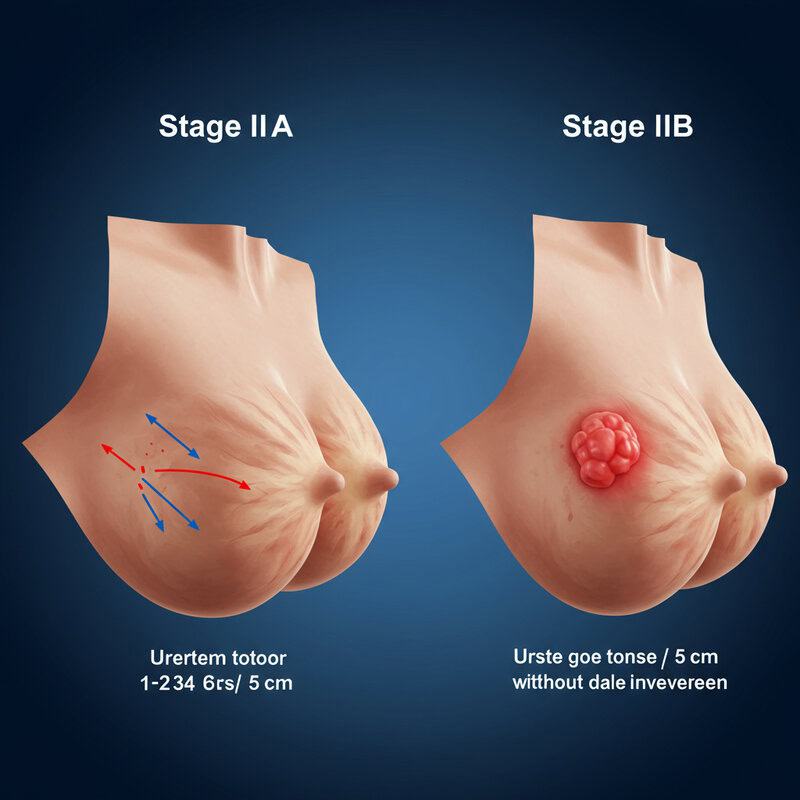

8. Stage IIA vs. IIB

Stage II breast cancer is divided into IIA and IIB, each defined by specific criteria regarding tumor size and lymph node involvement. Recognizing these distinctions is crucial for selecting the most effective treatment and understanding prognosis.

Stage IIA: In this substage, the tumor may be 2 centimeters or smaller and has spread to 1-3 axillary lymph nodes, or it may be between 2 and 5 centimeters with no lymph node involvement. The presence of cancer in a small number of lymph nodes or a moderately sized tumor helps guide decisions regarding the need for additional therapies such as chemotherapy or radiation.

Stage IIB: This subcategory includes tumors between 2 and 5 centimeters that have spread to 1-3 axillary lymph nodes, or tumors larger than 5 centimeters with no lymph node involvement. The increased tumor size or moderate lymph node involvement indicates a higher risk of recurrence and may require more aggressive treatment approaches.

Both substages remain localized without distant spread, but the differences in tumor size and nodal status influence therapeutic choices and prognosis. For further clarification on these staging categories, visit the National Cancer Institute’s breast cancer staging resource.

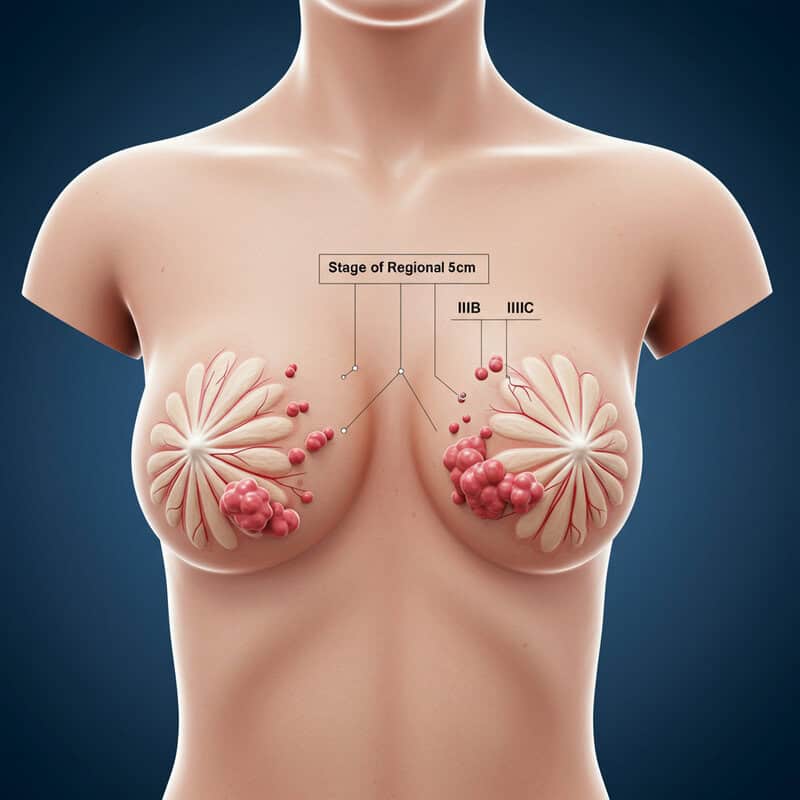

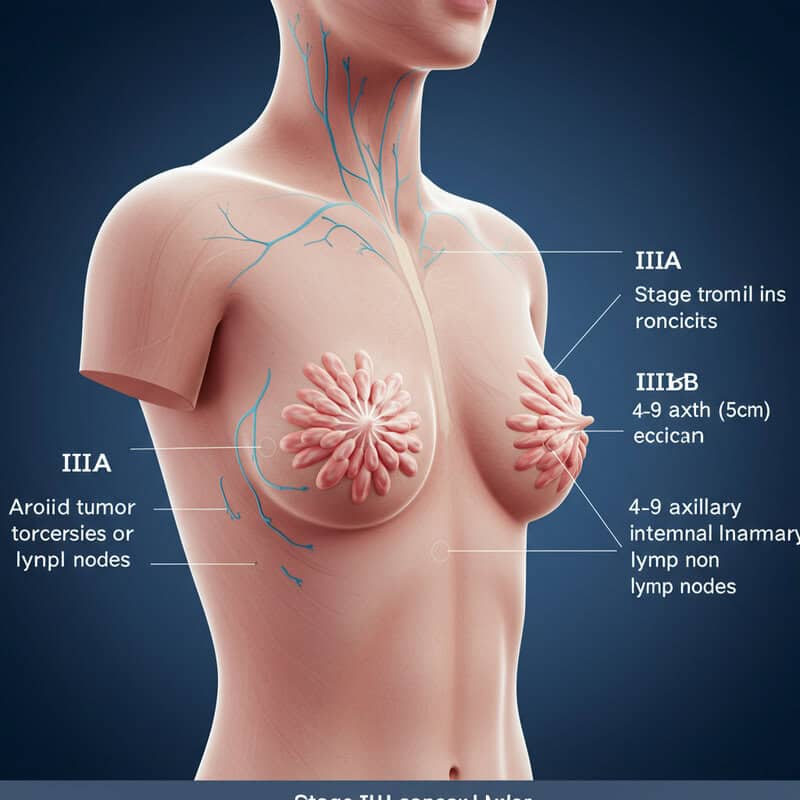

9. Stage III: Regional Spread

Stage III breast cancer signifies a more advanced disease, where the cancer has extended beyond the initial tumor site to involve nearby tissues or a greater number of lymph nodes, but has not yet metastasized to distant organs. This stage is further categorized into IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC, each reflecting varying degrees of regional spread.

Stage IIIA: Involves either a larger tumor (over 5 centimeters) with limited lymph node involvement, or smaller tumors with more extensive lymph node spread—often up to 9 axillary lymph nodes or internal mammary nodes.

Stage IIIB: Cancer has invaded the chest wall or skin, causing swelling or ulceration. It may also involve up to 9 nearby lymph nodes. Inflammatory breast cancer, a rare but aggressive form, can also be classified as IIIB.

Stage IIIC: Indicates even more extensive nodal involvement, with cancer found in 10 or more axillary lymph nodes, or in lymph nodes above or below the collarbone, but without distant metastasis.

Stage III cancers are considered regionally advanced and typically require a combination of treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapies. For detailed staging information, visit the Breastcancer.org Stage III Overview.

10. Stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC

Stage III breast cancer is divided into three subcategories—IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC—each defined by the extent of tumor growth and the involvement of lymph nodes and nearby structures.

Stage IIIA: This stage may involve a tumor larger than 5 centimeters that has spread to 1-3 axillary lymph nodes, or any size tumor with cancer in 4-9 axillary lymph nodes or internal mammary lymph nodes. The key feature is significant but still regional nodal involvement, elevating the risk of recurrence.

Stage IIIB: Here, the cancer has penetrated the chest wall and/or skin, causing swelling, inflammation, or ulceration. It may or may not involve up to 9 lymph nodes. Inflammatory breast cancer, characterized by redness and swelling of the breast, is often classified as IIIB due to its aggressive nature.

Stage IIIC: Cancer cells are found in 10 or more axillary lymph nodes, lymph nodes above or below the collarbone, or in internal mammary nodes. Tumor size can vary, but extensive lymph node involvement is the defining feature. Despite this spread, there is still no evidence of distant metastasis.

For a comprehensive overview of Stage III breast cancer subcategories, visit the American Cancer Society’s breast cancer stages page.

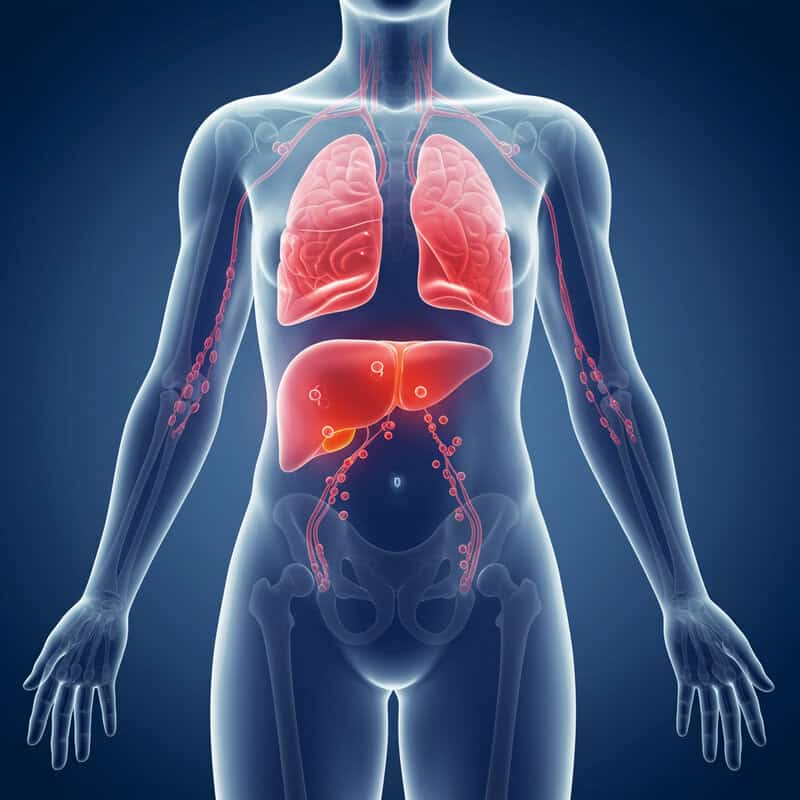

11. Stage IV: Distant Metastasis

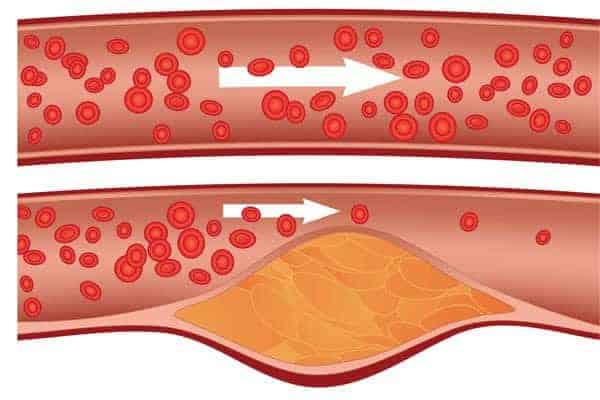

Stage IV breast cancer, also known as metastatic or advanced breast cancer, is characterized by the spread of cancer cells beyond the breast and nearby lymph nodes to distant organs in the body. Common sites of metastasis include the bones, liver, lungs, and brain. At this stage, cancer cells have traveled through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, establishing new tumors in other organs or tissues.

Unlike earlier stages, Stage IV is not considered curable, but it is treatable. The primary goals of treatment are to control the spread of the disease, relieve symptoms, and improve or maintain quality of life. Treatment plans may include systemic therapies such as hormone therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. The approach is highly individualized, taking into account the location and extent of metastasis, as well as the tumor’s biological characteristics.

Despite its advanced nature, many individuals with metastatic breast cancer can live for several years with appropriate treatment and supportive care. Ongoing research continues to improve outcomes and expand therapeutic options. For a detailed discussion of Stage IV breast cancer, visit the Breastcancer.org Stage IV resource.

12. Tumor Size Measurement

Tumor size is a fundamental factor in breast cancer staging and is typically measured as the largest dimension of the tumor in centimeters. Accurate assessment of tumor size often begins with imaging techniques such as mammography, ultrasound, or MRI, which help estimate the tumor’s extent before surgery. However, the most definitive measurement is obtained during pathological examination after surgical removal, where a pathologist measures the tumor directly using a ruler or caliper.

The size of the tumor is crucial because it helps determine the cancer’s stage and guides treatment decisions. Smaller tumors (usually 2 centimeters or less) are associated with earlier stages (such as Stage I), better prognosis, and a broader range of less aggressive treatment options. As tumor size increases, the stage may advance (moving from Stage I to II or III), and the risk of spread to lymph nodes or distant organs rises, often necessitating more intensive therapies.

Understanding tumor size is therefore essential for prognosis, treatment planning, and predicting outcomes. For more information on how tumor size influences staging, visit the American Cancer Society’s guide to breast cancer stages.

13. Lymph Node Involvement

Lymph node involvement is a critical component in breast cancer staging and significantly impacts prognosis. The lymphatic system, which includes lymph nodes and vessels, acts as a pathway for cancer cells to travel from the primary tumor to other parts of the body. During staging, physicians assess whether cancer has spread to the nearby lymph nodes—particularly those in the underarm (axillary nodes), around the collarbone (supraclavicular and infraclavicular nodes), and near the breastbone (internal mammary nodes).

The number of affected lymph nodes, as well as the size of cancer deposits within them, directly influences the stage of breast cancer. For example, the presence of cancer in 1-3 axillary lymph nodes may indicate Stage II, while involvement of 4-9 nodes can elevate the cancer to Stage III. More extensive nodal spread, especially to nodes above or below the collarbone, is associated with more advanced stages and a higher risk of recurrence.

Lymph node status also guides treatment choices, such as the need for chemotherapy, radiation, or targeted therapies. The more lymph nodes affected, the more aggressive the treatment approach is likely to be. For more details, consult the National Cancer Institute’s breast cancer staging resource.

14. Metastatic Sites

When breast cancer becomes metastatic, it means cancer cells have traveled from the primary tumor in the breast to distant organs or tissues through the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Understanding the most common metastatic sites is essential for both prognosis and treatment planning, as symptoms and management options can vary depending on where the cancer has spread.

Bone: The bones are the most frequent site of breast cancer metastasis, particularly the spine, pelvis, ribs, and long bones in the arms and legs. Bone metastases can cause pain, fractures, and high calcium levels in the blood.

Liver: The liver is another common site. Metastasis here can cause symptoms like abdominal pain, jaundice, and changes in liver function tests.

Lungs: The lungs are frequently affected, sometimes leading to cough, shortness of breath, or chest pain.

Brain: While less common than bone or liver, brain metastases can cause headaches, neurological symptoms, or seizures.

Early detection of metastatic spread is vital for effective management and symptom control. For more information, visit the Breastcancer.org page on metastatic breast cancer.

15. Hormone Receptor Status

Hormone receptor status is a crucial factor in breast cancer evaluation, influencing both staging and treatment decisions. Breast cancer cells are tested for the presence of hormone receptors—specifically estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR). Tumors that test positive for these receptors are referred to as “hormone receptor-positive.” These tumors depend on hormones to grow and are more likely to respond to hormone-blocking therapies.

While hormone receptor status does not directly alter the anatomic stage of breast cancer, it plays a significant role in overall staging and prognosis. Hormone receptor-positive cancers tend to grow more slowly and have a better outlook than hormone receptor-negative types. The presence or absence of these receptors is considered in the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s (AJCC) prognostic staging system, which helps provide a more tailored prediction of outcomes.

Knowing whether a tumor is ER or PR positive guides the use of hormone therapies such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors, which can significantly reduce recurrence risk and improve survival. This information is obtained through pathology testing of breast tissue samples. For further details, visit the American Cancer Society’s resource on hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

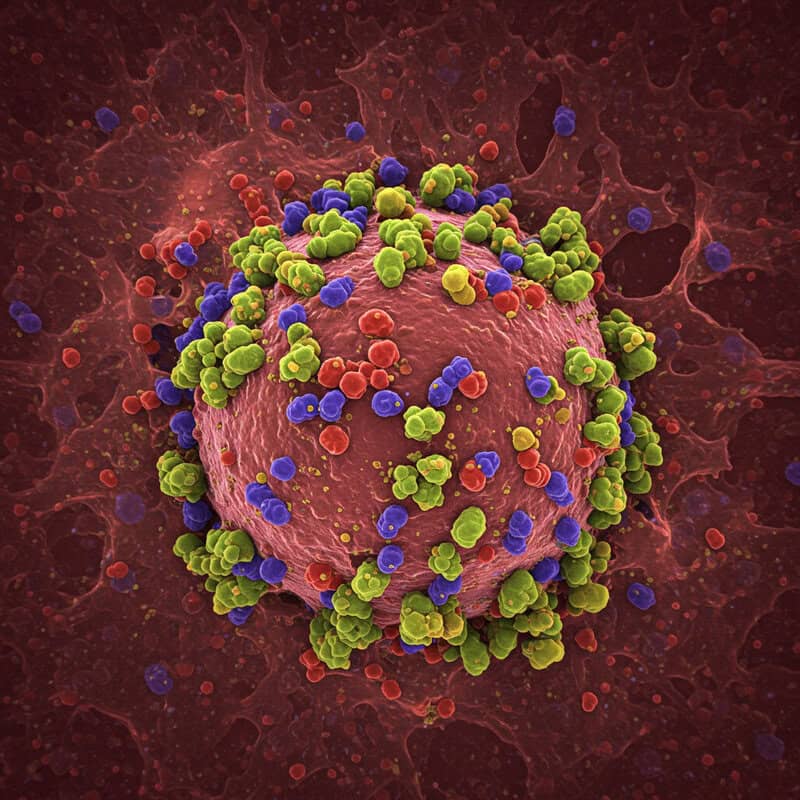

16. HER2 Status

HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) is a protein found on the surface of some breast cancer cells that promotes cell growth. In about 15-20% of breast cancers, the HER2 gene is amplified, resulting in an overproduction of the HER2 protein. These cancers are referred to as HER2-positive. Testing for HER2 status is performed using tissue samples obtained from a biopsy or surgery, typically through immunohistochemistry (IHC) or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) tests.

HER2-positive breast cancers tend to grow more quickly and may be more aggressive than HER2-negative cancers. However, the prognosis for HER2-positive patients has improved dramatically with the introduction of targeted therapies such as trastuzumab (Herceptin), pertuzumab, and other HER2 inhibitors. Knowing a tumor’s HER2 status is essential for guiding treatment, as these targeted drugs can significantly reduce the risk of recurrence and improve survival rates.

HER2 status, along with hormone receptor status and tumor grade, is incorporated into modern breast cancer staging and is vital for personalizing therapy. For more information on HER2 testing and its implications, visit the Breastcancer.org HER2 resource.

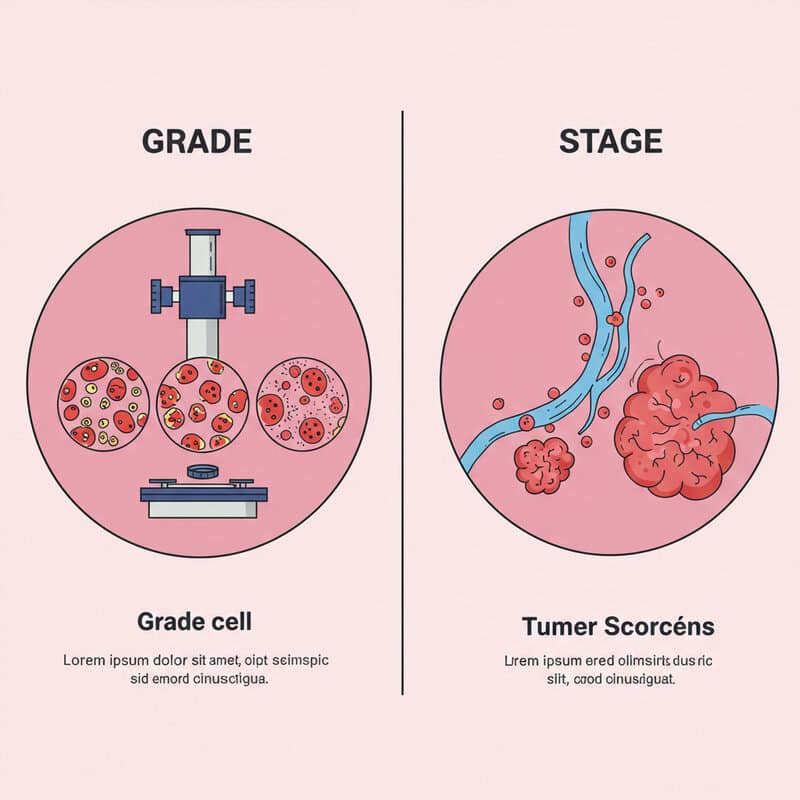

17. Grade vs. Stage

The terms “grade” and “stage” in breast cancer may sound similar, but they refer to distinct aspects of the disease. Tumor grade describes how cancer cells look under a microscope compared to normal breast cells. It provides insight into how quickly the tumor is likely to grow and spread. Tumors are usually graded on a scale of 1 to 3:

Grade 1 (low grade): Cancer cells resemble normal cells and tend to grow slowly.

Grade 2 (intermediate grade): Cells are somewhat abnormal and grow at a moderate rate.

Grade 3 (high grade): Cells look very different from normal and tend to grow and spread more aggressively.

In contrast, cancer stage refers to the extent of cancer in the body — specifically, tumor size, lymph node involvement, and whether it has spread to distant organs. While stage indicates how far the cancer has progressed, grade provides information on its likely behavior. Both factors are important for determining prognosis and choosing the most effective treatment. For a deeper understanding, visit the Cancer.Net overview of breast cancer stages and grades.

18. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a distinct subtype that lacks estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and HER2 protein overexpression. Because TNBC does not respond to hormone therapies or HER2-targeted treatments, it presents unique challenges in both treatment and staging. TNBC accounts for about 10-15% of all breast cancers and is more common in younger women and those with BRCA1 gene mutations.

While the anatomic staging (tumor size, lymph node involvement, and metastasis) for TNBC is the same as for other breast cancers, its aggressive nature and higher likelihood of early spread require special consideration. TNBC tends to progress more quickly, with a greater risk of recurrence, particularly within the first few years after diagnosis. As a result, clinicians often recommend more aggressive treatment strategies, typically involving surgery, chemotherapy, and sometimes clinical trials with immunotherapy or novel agents.

Prognosis for TNBC is generally less favorable than for hormone receptor-positive or HER2-positive cancers, especially in advanced stages. Early detection and prompt, comprehensive treatment are critical for improving outcomes. For more information on triple-negative breast cancer, visit the Breastcancer.org Triple-Negative Breast Cancer resource.

19. Inflammatory Breast Cancer

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare and aggressive form of breast cancer that accounts for 1-5% of all breast cancer cases. Unlike typical breast cancers that form a distinct lump, IBC typically spreads rapidly and presents with symptoms such as redness, swelling, warmth, and skin thickening, giving the breast a “peau d’orange” (orange peel) appearance. These symptoms are caused by cancer cells blocking lymph vessels in the skin.

Due to its unique presentation and rapid progression, IBC is staged differently from other breast cancers. It is always classified as at least Stage IIIB, regardless of tumor size, because it involves the skin and often the chest wall. If cancer is found in the lymph nodes above or below the collarbone or in distant organs, the staging may be IIIC or IV, respectively. Early detection is challenging, and IBC is frequently diagnosed at a more advanced stage.

Treatment for IBC is typically aggressive, involving a combination of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy, with additional targeted therapies when appropriate. For more detailed information, visit the American Cancer Society’s resource on inflammatory breast cancer.

20. Paget Disease of the Nipple

Paget disease of the nipple is a rare form of breast cancer, accounting for about 1-3% of all breast cancer cases. It typically presents with symptoms affecting the nipple and areola, such as redness, flaking, itching, tingling, and sometimes a burning sensation. In more advanced cases, ulceration, oozing, or bleeding from the nipple may occur. These changes are often mistaken for benign skin conditions like eczema, which can delay diagnosis.

Paget disease almost always indicates the presence of underlying breast cancer, either ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or invasive breast cancer. The staging of Paget disease depends on the characteristics of the underlying tumor. If only DCIS is present beneath the nipple, the cancer may be classified as Stage 0. However, if invasive cancer is found, staging will be based on the size of the tumor and the extent of lymph node involvement or metastasis, similar to other breast cancer types.

Early recognition and biopsy of persistent nipple or areolar changes are crucial for timely management. Treatment may involve surgery, radiation therapy, and additional therapies depending on the stage and type of underlying cancer. For more information, visit the Breastcancer.org Paget Disease resource.

21. Male Breast Cancer Staging

Although breast cancer is far less common in men than in women, accounting for less than 1% of all breast cancer cases, the staging principles remain largely the same. The TNM system—evaluating tumor size (T), lymph node involvement (N), and metastasis (M)—is used to determine the stage of breast cancer in men just as it is in women. However, there are some important distinctions to consider.

Because men have less breast tissue, tumors may more quickly invade nearby structures or reach the skin and chest wall, sometimes leading to diagnosis at a more advanced stage. Lymph node involvement is also common at presentation, partly due to delays in recognition and diagnosis. The smaller volume of male breast tissue can mean that even small tumors are located close to the nipple or chest wall, impacting surgical options and staging.

Hormone receptor status and HER2 status are just as critical in male breast cancer, influencing treatment with hormone therapies or targeted agents. Awareness of male breast cancer symptoms and timely evaluation are essential for improving outcomes. For more information and resources, visit the American Cancer Society’s section on male breast cancer.

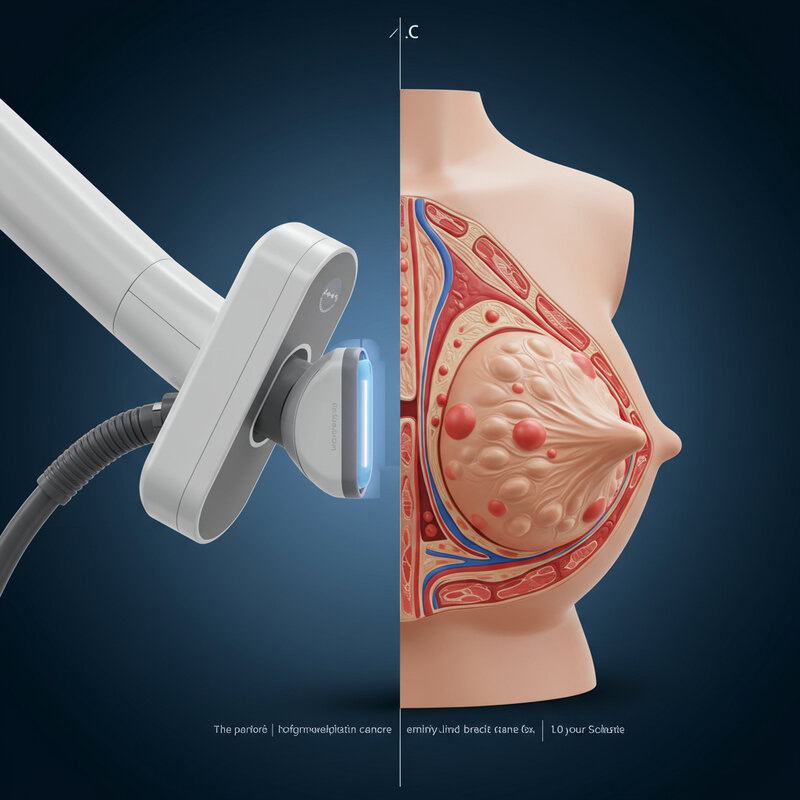

22. Diagnostic Imaging Tools

Diagnostic imaging plays a pivotal role in the staging of breast cancer, enabling clinicians to assess tumor size, evaluate lymph node involvement, and detect possible metastasis. The primary imaging modalities used in breast cancer workups include mammograms, ultrasounds, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Mammograms: These X-ray images of the breast are the standard screening and diagnostic tool for detecting abnormalities. Mammograms help determine the location, size, and characteristics of breast tumors and can identify suspicious areas that may require further evaluation.

Ultrasound: Breast ultrasound uses sound waves to create detailed images, making it useful for distinguishing between solid tumors and fluid-filled cysts. It is also employed to assess lymph nodes in the axilla (underarm) and guide biopsy procedures.

MRI: Breast MRI provides highly detailed images using magnetic fields and is particularly valuable for evaluating the extent of disease in dense breast tissue, identifying multifocal or multicentric tumors, and screening high-risk individuals. MRI is also useful for preoperative planning and monitoring response to therapy.

For more information on breast imaging in cancer staging, visit the RadiologyInfo.org breast cancer imaging page.

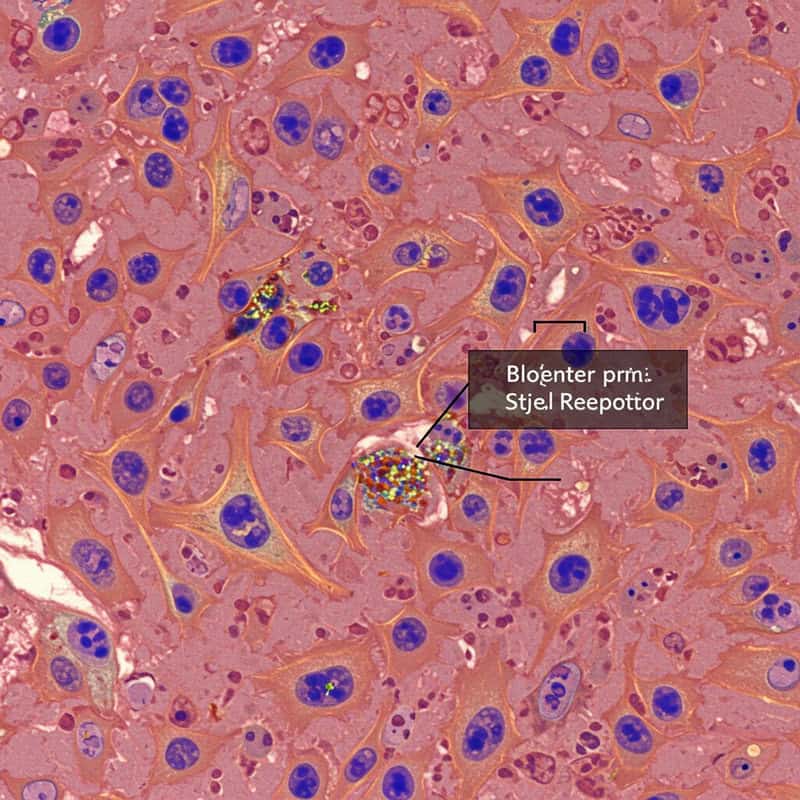

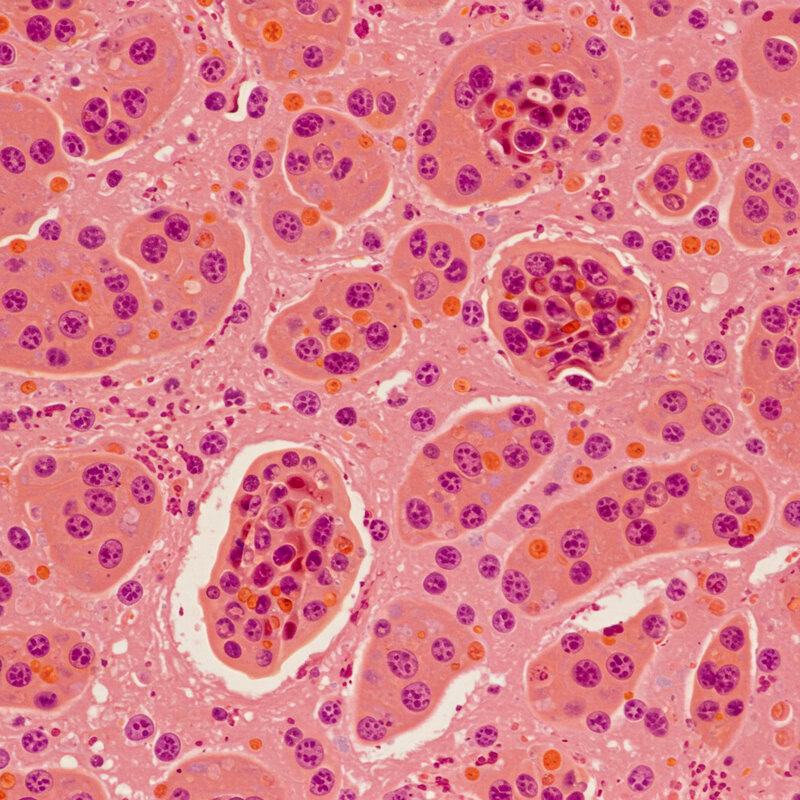

23. Biopsy and Pathology Reports

Biopsies are fundamental to the accurate staging of breast cancer. A biopsy involves removing a sample of tissue from the suspicious area in the breast or lymph nodes, which is then analyzed by a pathologist. The most common types include core needle biopsy, fine needle aspiration, and surgical (excisional) biopsy. The choice of biopsy technique depends on the tumor’s size, location, and imaging characteristics.

The resulting pathology report provides essential information that drives staging decisions. It details the type of breast cancer, tumor size, grade, and the presence or absence of cancer cells in the lymph nodes. Pathology also determines hormone receptor status (estrogen and progesterone) and HER2 protein expression, both of which are crucial for prognosis and guiding targeted treatments.

Additionally, the pathologist assesses surgical margins (the edges of the removed tissue) to ensure the entire tumor has been excised. If lymph nodes are sampled, the report specifies how many were involved and the extent of cancer spread. This thorough evaluation allows clinicians to accurately assign a cancer stage and formulate a personalized treatment plan. For more information on understanding pathology reports, visit the Breastcancer.org pathology report resource.

24. Genomic Tests and Staging

Genomic testing has become increasingly important in the management and staging of breast cancer. Unlike traditional pathology, which examines the appearance and markers of cancer cells, genomic tests analyze the activity of specific groups of genes within the tumor. These tests can help predict the risk of recurrence and guide treatment decisions, particularly in early-stage, hormone receptor-positive breast cancers.

Commonly used genomic assays include Oncotype DX, MammaPrint, and Prosigna. These tests evaluate gene expression profiles to estimate the likelihood of cancer returning after initial treatment. For example, the Oncotype DX test provides a recurrence score that helps assess the benefit of adding chemotherapy to hormone therapy for certain patients. Genomic test results are not part of the traditional TNM staging system, but they complement anatomical staging by offering personalized risk assessments.

This evolving approach enables oncologists to tailor therapy more precisely, sparing some patients from unnecessary treatments and identifying others who may benefit from more aggressive interventions. For more information on how genomic tests are shaping breast cancer care and risk stratification, visit the National Cancer Institute’s guide to genomic testing in breast cancer.

25. Staging After Surgery

Surgical intervention is a crucial step not only for treating breast cancer but also for refining cancer staging. When a tumor and surrounding lymph nodes are surgically removed, pathologists can carefully examine the tissues, providing more precise information than preoperative imaging or needle biopsies alone. This process is known as pathological or post-surgical staging.

Pathological staging can reveal important details, such as the exact tumor size, the number of lymph nodes involved, and whether cancer cells have invaded blood vessels or lymphatics. Sometimes, surgery uncovers more extensive disease than initially suspected, or conversely, it confirms a lower stage if fewer lymph nodes are involved or the tumor is smaller than imaging suggested. As a result, a patient’s stage may be “upstaged” or “downstaged” after surgery, influencing recommendations for additional therapies like chemotherapy, radiation, or hormone therapy.

This updated staging, often called “pathologic stage” (pTNM), becomes the definitive guide for subsequent treatment and prognosis. Accurate post-surgical staging ensures that patients receive the most appropriate and effective care. For further reading, see the American Cancer Society’s explanation of breast cancer staging after surgery.

26. Restaging With Recurrence

When breast cancer returns after initial treatment, the process of evaluating its extent is known as restaging. Recurrence can occur locally (in the same breast or chest wall), regionally (nearby lymph nodes), or at distant sites (such as bones, liver, lungs, or brain). Unlike the original diagnosis, the stage assigned at recurrence does not replace the original stage but is described as “recurrent” or “metastatic.”

Restaging involves a thorough clinical assessment, imaging studies (such as CT, PET, MRI, or bone scans), and often biopsies to confirm the presence and characteristics of recurrent cancer. The purpose of restaging is to determine the location, size, and spread of the recurrence so that an appropriate treatment plan can be developed. If the cancer reappears at a distant site, it is classified as metastatic, regardless of the original stage.

Restaging also helps identify changes in tumor biology—such as hormone receptor or HER2 status—which can sometimes differ from the original cancer and influence subsequent therapy. For more information about breast cancer recurrence and restaging, visit the American Cancer Society’s resource on recurrent breast cancer.

27. Staging and Survival Rates

The stage at which breast cancer is diagnosed is one of the most significant factors influencing survival rates and long-term prognosis. Generally, the earlier the stage at diagnosis, the higher the likelihood of successful treatment and long-term survival. For example, according to data from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER Program, the 5-year relative survival rate for women diagnosed with localized breast cancer (Stages 0 and I) is about 99%.

As the cancer stage advances, survival rates decrease. For regional breast cancer (Stage II and III), where the disease has spread to nearby lymph nodes or tissues, the 5-year survival rate drops to approximately 86%. In cases of distant or metastatic breast cancer (Stage IV), where cancer has spread to organs such as the bones, liver, or lungs, the 5-year relative survival rate is roughly 31%.

These statistics underscore the importance of early detection and prompt treatment. Prognosis can also be influenced by tumor biology, patient age, overall health, and advances in treatment. For a detailed overview of survival rates by stage, refer to the American Cancer Society’s survival statistics.

28. Early Detection and Staging

Early detection of breast cancer through regular screening is a critical factor in diagnosing the disease at an earlier, more treatable stage. Screening methods such as mammography, clinical breast exams, and, in high-risk individuals, breast MRI, can identify abnormalities before symptoms develop. When breast cancer is discovered early—typically at Stage 0 (DCIS) or Stage I—it is usually smaller, less likely to have spread to lymph nodes, and associated with a significantly higher chance of successful treatment and long-term survival.

Multiple studies have shown that populations with widespread access to regular screening programs experience a greater proportion of breast cancers diagnosed at localized stages and lower overall mortality rates. Early-stage detection not only improves prognosis but also allows for a wider range of less aggressive treatment options, reducing the likelihood of extensive surgery or chemotherapy.

Health organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Cancer Society recommend regular screening as the best strategy for catching breast cancer early and improving outcomes. Timely screening and follow-up remain essential tools in reducing the impact of breast cancer.

29. Staging and Treatment Choices

The stage of breast cancer at diagnosis is a primary factor in determining the most appropriate and effective treatment strategy. Early-stage cancers (Stages 0, I, and some II) are typically managed with local therapies, such as surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy) and, in many cases, radiation therapy. The goal at these stages is to remove or destroy the tumor while preserving as much normal tissue as possible. Adjuvant systemic therapies, including hormone therapy or targeted therapy, may be recommended based on tumor biology, even in early stages, to reduce the risk of recurrence.

For more advanced stages (later Stage II, III), a combination of treatments is generally required. Surgery is often preceded or followed by chemotherapy, and radiation therapy may be used to control local and regional disease. In Stage IV (metastatic) breast cancer, systemic therapies—such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted agents, or immunotherapy—are the mainstay, with surgery and radiation typically reserved for symptom relief or specific complications.

Accurate staging ensures that patients receive individualized care tailored to the extent of their disease. For an in-depth look at how staging informs treatment options, visit the National Cancer Institute’s breast cancer treatment guide.

30. Personalized Staging Approaches

Modern breast cancer staging is rapidly evolving beyond just anatomic criteria to integrate molecular and genetic information, enabling a more personalized approach to care. In addition to tumor size, lymph node status, and presence of metastasis, clinicians now routinely consider tumor biology—such as hormone receptor status, HER2 expression, and even multigene assay results—to refine prognosis and guide treatment decisions.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) introduced “prognostic staging,” which incorporates these molecular markers alongside traditional TNM factors, offering more nuanced insights into disease behavior and patient outcomes. Genomic tests like Oncotype DX or MammaPrint can further stratify risk, helping to determine which patients are likely to benefit from chemotherapy or may safely avoid it. This integration of molecular profiling leads to increasingly individualized treatment plans, minimizing overtreatment and maximizing benefit.

Personalized staging approaches ensure that each patient’s cancer is evaluated in the context of its unique biological characteristics, resulting in more precise predictions of outcome and more targeted therapy recommendations. For the latest on personalized breast cancer staging and prognostic tools, visit the National Cancer Institute’s overview of AJCC’s personalized staging.

31. Staging in Young Women

Breast cancer in women under 40 presents unique challenges for staging and management. Younger women often have denser breast tissue, making detection via mammography more difficult and sometimes leading to diagnoses at more advanced stages. Additionally, breast cancers in this age group are more likely to be biologically aggressive, such as triple-negative or HER2-positive subtypes, increasing the risk of early spread and recurrence.

Staging in young women follows the same TNM and molecular criteria as in older patients, but the implications may differ. For example, fertility preservation, genetic counseling, and psychosocial support are critical considerations during the staging and treatment process. Young women are more likely to have hereditary breast cancer linked to BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations, which can influence both staging and long-term management strategies.

Because of these factors, a multidisciplinary approach is essential to ensure comprehensive care. Early and accurate staging allows for timely, tailored interventions that can improve outcomes. For more information on the unique aspects of breast cancer in young women, visit the Breastcancer.org resource on young women and breast cancer.

32. Staging in Older Adults

Staging breast cancer in older adults involves not only assessing the extent of disease but also considering age-related factors and comorbid conditions. Older patients may present with lower-stage cancers due to regular screening, or conversely, with more advanced disease if screening has been limited or symptoms overlooked. Age alone does not change the TNM staging, but comorbidities such as heart disease, diabetes, or reduced organ function can impact the staging workup, choice of diagnostic tools, and treatment planning.

Treatment decisions in older adults are often individualized to balance the potential benefits and risks, taking into account life expectancy, overall health, cognitive function, and patient preferences. Some older adults may tolerate standard therapies well, while others may require modified or less aggressive approaches. The biology of tumors in older adults may also differ, with a higher likelihood of hormone receptor-positive cancers that respond well to hormone therapy.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary collaboration are essential for optimal care. For further information on the specific considerations and best practices for staging and treating breast cancer in older patients, visit the American Cancer Society’s resource on breast cancer in older women.

33. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Staging

Significant racial and ethnic disparities persist in breast cancer staging and outcomes across populations. Research shows that Black women in the United States are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages of breast cancer compared to white women, contributing to higher mortality rates. Factors such as reduced access to screening, differences in healthcare utilization, socioeconomic barriers, and systemic inequities play a role in these disparities.

Hispanic, Native American, and some Asian populations also experience higher rates of late-stage diagnosis compared to non-Hispanic whites. Delayed access to care, cultural beliefs, language barriers, and lack of insurance may further impact timely detection and treatment. Moreover, certain aggressive subtypes, like triple-negative breast cancer, are more prevalent in Black women, increasing the likelihood of early spread and advanced staging at diagnosis.

Efforts to address these disparities focus on improving access to screening, patient education, community outreach, and culturally competent care. Recognizing and actively addressing these factors is vital for reducing gaps in breast cancer outcomes. For more information on disparities in breast cancer staging and survival, visit the American Cancer Society’s page on breast cancer disparities.

34. Global Differences in Staging

Breast cancer staging practices and outcomes can vary significantly across countries due to differences in healthcare infrastructure, access to diagnostic tools, and public health policies. In high-income countries with established screening programs—such as the United States, Western Europe, and Australia—most breast cancers are detected at earlier stages, leading to better survival rates and more treatment options. Access to advanced imaging, pathology, and molecular testing further enhances the accuracy of staging in these regions.

In contrast, low- and middle-income countries often face challenges such as limited access to screening, delayed diagnoses, and fewer resources for comprehensive staging workups. As a result, a higher proportion of women in these regions present with late-stage or metastatic disease, which negatively impacts prognosis and survival. Socioeconomic barriers, cultural beliefs, and lack of awareness further contribute to differences in stage at diagnosis.

Efforts to improve early detection and standardized staging—such as the implementation of global guidelines by organizations like the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC)—are crucial for reducing disparities. For more data and insight on international breast cancer staging and outcomes, visit the World Health Organization’s breast cancer fact sheet.

35. Clinical Trials and Staging Criteria

Accurate breast cancer staging is essential for participation in clinical trials, which are critical to advancing treatment and improving outcomes. Clinical trials often specify detailed staging criteria to ensure that participants have similar disease characteristics, allowing researchers to accurately assess the effectiveness and safety of new therapies. For example, some trials may be limited to patients with early-stage disease, while others focus on those with advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

Staging information—including tumor size, lymph node status, and the presence of metastasis—helps determine eligibility and stratifies patients into appropriate study groups. Molecular and genomic markers, such as hormone receptor and HER2 status, are increasingly included in eligibility criteria to tailor studies to specific cancer subtypes. This precision ensures that study results are applicable to the intended patient populations and that therapies are tested in the groups most likely to benefit.

Participation in clinical trials can offer access to cutting-edge treatments and contribute valuable data to the global understanding of breast cancer. For more information on clinical trial eligibility and the role of staging, visit the National Cancer Institute’s guide to clinical trials.

36. Updates in Staging Guidelines

Recent years have seen significant updates in breast cancer staging guidelines, reflecting advances in molecular biology and targeted therapies. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) introduced the 8th edition of its staging manual, which incorporates not only the traditional anatomic TNM system but also prognostic factors such as hormone receptor status, HER2 expression, and tumor grade. This “prognostic staging” approach enables clinicians to provide more individualized predictions of outcomes and tailor treatments accordingly.

Expert panels now emphasize the integration of molecular and genomic information into routine staging, acknowledging that two patients with the same anatomic stage may have very different prognoses and treatment needs based on tumor biology. The inclusion of multigene assays, such as Oncotype DX and MammaPrint, further refines risk stratification and guides adjuvant therapy decisions for early-stage, hormone receptor-positive cancers.

These guideline updates are supported by organizations such as the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Staying current with staging recommendations is vital for clinicians and patients to ensure optimal, evidence-based care in the rapidly evolving landscape of breast cancer management.

37. Psychosocial Impact of Staging

Learning one’s breast cancer stage is a pivotal moment that can bring about a wide range of emotional and psychological responses. For many patients, the diagnosis and subsequent staging process are accompanied by anxiety, fear, and uncertainty about the future. The stage of cancer often shapes initial perceptions of prognosis, treatment intensity, and chances of recovery, making the disclosure of this information highly impactful.

Receiving an early-stage diagnosis can offer relief and hope but may still provoke distress about treatment side effects and the risk of recurrence. Conversely, being diagnosed with advanced or metastatic disease can trigger feelings of grief, depression, and existential worry. Patients may also experience stress related to treatment decisions, family dynamics, work, and financial concerns. The support of mental health professionals, social workers, and peer support groups is crucial in helping individuals process the emotional burden associated with staging.

Open communication with healthcare providers and access to psychosocial resources can alleviate distress and foster resilience. For more information on the emotional impact of breast cancer and available support services, visit the American Cancer Society’s page on the emotional side effects of breast cancer.

38. Communicating Stage to Patients

Effectively communicating a breast cancer stage to patients is a sensitive and essential part of the oncology care process. Healthcare teams strive to convey information clearly, empathetically, and in a manner tailored to each patient’s level of understanding and emotional readiness. This typically involves using straightforward language free of jargon, providing visual aids or written materials, and allowing ample time for questions.

Clinicians often explain what the stage means in terms of tumor size, lymph node involvement, and whether the cancer has spread, relating these factors to prognosis and treatment options. They emphasize that staging is only one component of the overall picture and discuss how additional tumor characteristics, such as hormone receptor and HER2 status, influence care. Many providers use diagrams or staging charts to help patients visualize their diagnosis.

Open communication fosters trust and empowers patients to participate actively in treatment planning. It is also important for clinicians to assess patient understanding, address emotional responses, and offer access to support resources. For strategies and tips on discussing diagnosis and staging, visit the National Cancer Institute’s guide on talking about cancer.

39. Patient Stories: Early Stage

Maria, a 45-year-old mother of two, discovered her breast cancer during a routine screening mammogram. She had no symptoms and no family history of the disease. The radiologist noticed a small abnormality, and a follow-up biopsy confirmed Stage I invasive ductal carcinoma. Maria’s care team explained that her cancer was small, had not spread to the lymph nodes, and was hormone receptor-positive, making her prognosis excellent.

After a lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy, Maria required only a short course of radiation therapy and began hormone therapy to reduce her risk of recurrence. She returned to work within weeks and continues to have regular follow-up appointments. Maria credits early detection and the support of her healthcare team for her positive outcome and encourages others to prioritize regular screening.

Stories like Maria’s highlight the benefits of early stage diagnosis—less aggressive treatment, faster recovery, and a high likelihood of long-term survival. For more real-life accounts and support, visit the Breastcancer.org Personal Stories page, where patients share their journeys, challenges, and successes at various stages of breast cancer.

40. Patient Stories: Late Stage

Denise, a 52-year-old graphic designer, was diagnosed with Stage IV breast cancer after experiencing persistent back pain and fatigue. Initially attributing her symptoms to stress and long work hours, she delayed seeking medical attention. Imaging and biopsy revealed metastatic breast cancer that had spread to her bones and liver. The diagnosis was overwhelming and brought a flood of emotions—fear, uncertainty, and grief about her future.

Denise’s oncology team explained the goals of treatment: to control the disease, manage symptoms, and maintain her quality of life. She began systemic therapy, including targeted treatments and bone-strengthening medications, and joined a support group for people living with metastatic cancer. Through ongoing treatment and the encouragement of her care team, Denise has been able to continue working and remain active in her community.

Her story underscores the realities faced by those diagnosed at a late stage, including complex treatment decisions and the importance of psychosocial support. Denise’s journey is a testament to resilience and the advances in therapy that can extend life and improve well-being. For more personal stories and resources for those living with metastatic breast cancer, visit the American Cancer Society’s advanced breast cancer stories.

41. Second Opinions and Staging

Seeking a second medical opinion after a breast cancer diagnosis—and particularly regarding staging—can provide valuable reassurance and clarity for patients. A second opinion allows another specialist to review pathology slides, imaging studies, and clinical findings, which may confirm the original stage or, in some cases, identify discrepancies that could impact treatment decisions. This additional perspective can be especially helpful in complex or borderline cases, such as when the cancer is near a stage boundary or when rare subtypes like inflammatory or triple-negative breast cancer are involved.

The process typically involves requesting medical records, imaging, and pathology reports from your current provider and arranging a consultation with another oncologist, often at a different cancer center. Most physicians support and even encourage second opinions, recognizing that they empower patients to make informed choices about their care.

Second opinions can lead to changes in staging, revised treatment recommendations, or simply peace of mind. Some insurance plans may require or cover the cost of second opinions, especially for major diagnoses. For more on the benefits and logistics of seeking a second opinion, visit the American Cancer Society’s guide to second opinions.

42. Role of Multidisciplinary Teams

Multidisciplinary teams are central to the modern management of breast cancer, ensuring that staging and treatment planning are comprehensive, accurate, and tailored to the individual patient. These teams typically include medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, genetic counselors, nurses, and social workers. Together, they review imaging studies, biopsy results, pathology reports, and molecular testing to achieve consensus on the precise stage of cancer.

Collaboration within a multidisciplinary team helps integrate diverse expertise, leading to well-rounded assessments and the formulation of optimal treatment strategies. Regular tumor board meetings enable team members to discuss complex cases, resolve discrepancies in staging, and make collective decisions regarding surgery, systemic therapies, and supportive care. Genetic counselors may provide input on inherited risk factors, while social workers and nurse navigators address psychosocial and logistical concerns.

This team-based approach enhances communication, minimizes errors, and ensures that all aspects of a patient’s diagnosis and care are considered. Patients benefit from seamless coordination and access to a full spectrum of resources. For more on the value and structure of multidisciplinary breast cancer care, visit the National Cancer Institute’s overview of multidisciplinary care.

43. Staging and Health Insurance

The stage of breast cancer at diagnosis plays a significant role in determining health insurance coverage for treatments, diagnostics, and participation in clinical trials. Insurance providers often use staging information to approve or deny coverage for certain therapies, imaging studies, surgical procedures, and emerging treatments. For example, advanced-stage cancers may warrant more comprehensive imaging or access to novel drugs, while early-stage cancers might be managed with less intensive regimens.

Certain therapies, such as targeted agents or immunotherapies, are typically approved based on specific stage and tumor characteristics. Insurance companies may also require documentation of stage before authorizing coverage for reconstructive surgery, radiation therapy, or genetic testing. Additionally, eligibility for many clinical trials is linked to cancer stage, and insurance may cover routine care costs related to trial participation, as mandated by federal law in the United States.

Understanding one’s stage is crucial for navigating insurance approvals and appeals. Patients are encouraged to work closely with their oncology team and insurance representatives to ensure access to all recommended treatments. For detailed guidance on insurance and breast cancer, visit the American Cancer Society’s resource on health insurance and breast cancer.

44. Patient Advocacy in Staging

Patient advocates play a vital role in helping individuals understand and navigate the complexities of breast cancer staging and subsequent treatment decisions. These advocates, often survivors themselves or trained professionals, provide education, emotional support, and practical guidance throughout the diagnostic and care process. They help patients interpret staging terminology, explain the significance of test results, and ensure that questions are addressed during medical consultations.

Advocates empower patients to participate actively in their care, encouraging them to seek second opinions, explore clinical trial options, and communicate openly with their healthcare teams. They can assist with gathering and organizing medical records, preparing for appointments, and understanding insurance coverage related to stage-specific treatments. In addition, advocates often connect patients with support groups, legal resources, and financial assistance programs tailored to people at different stages of breast cancer.

By bridging gaps in understanding and fostering shared decision-making, patient advocates contribute to improved satisfaction and outcomes. Several organizations offer advocacy services and resources, including the National Breast Cancer Foundation’s Patient Navigation Program and the CancerCare Breast Cancer Support. These resources help ensure that every patient receives informed, compassionate, and stage-appropriate care.

45. Staging and Fertility Preservation

Fertility preservation is a critical consideration for premenopausal women diagnosed with breast cancer, and the cancer stage can significantly influence available options and timelines. Early-stage breast cancers (Stages 0-II) often allow for a brief window between diagnosis and the start of systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy or hormone therapy, during which fertility preservation procedures can be safely performed. Options include egg or embryo freezing (cryopreservation) and, in some cases, ovarian tissue preservation.

For patients with more advanced-stage disease (Stage III or IV), the urgency to begin treatment may limit the time available for fertility interventions. Additionally, certain aggressive cancers or those requiring immediate systemic therapy may further complicate decision-making. Oncologists and reproductive specialists collaborate closely to counsel patients about the risks of infertility due to cancer treatment and to tailor fertility preservation strategies to the individual’s clinical situation and stage.

Early referral to a fertility specialist is essential for young patients interested in maintaining future reproductive options. For further information on fertility and breast cancer, visit the Cancer.Net fertility preservation resource and the Breastcancer.org fertility guide.

46. Staging and Genetic Counseling

Genetic counseling is an important component of breast cancer care, particularly for patients whose cancer stage or family history suggests a hereditary risk. While the stage of cancer itself does not determine the need for genetic counseling, certain clinical scenarios—such as a diagnosis at a young age (usually under 50), triple-negative breast cancer, bilateral breast cancer, or advanced-stage disease—may prompt referral to a genetic counselor.

Patients with a strong family history of breast, ovarian, pancreatic, or prostate cancer, regardless of stage, are also candidates for genetic counseling and testing. Identifying inherited mutations in genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, or others can influence staging workups, surgical recommendations (such as consideration of bilateral mastectomy), and the use of targeted therapies like PARP inhibitors. Genetic information is also critical for guiding screening and preventive measures in family members.

Genetic counselors provide education, risk assessment, and support in interpreting test results. Early referral is recommended so that results can inform staging, treatment planning, and family counseling. To learn more about genetic counseling and breast cancer, visit the National Cancer Institute’s BRCA fact sheet and the Breastcancer.org genetics overview.

47. Staging and Lifestyle Adjustments

Learning one’s breast cancer stage often prompts a reevaluation of lifestyle choices to support both physical and emotional well-being during and after treatment. While recommended adjustments apply across all stages, specific changes may be emphasized based on prognosis, treatment side effects, and overall health goals.

For most patients, adopting a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains is encouraged to help maintain strength and promote healing. Regular physical activity, such as walking, yoga, or light resistance exercises, can improve energy, reduce fatigue, and enhance quality of life. Smoking cessation and moderation or avoidance of alcohol are especially important, as these factors can influence recurrence risk and overall health.

Managing stress through relaxation techniques, counseling, or support groups can be particularly helpful, especially for those coping with advanced-stage disease or intensive treatment regimens. Patients are also advised to follow prescribed medication schedules, attend all follow-up appointments, and communicate openly with their care team about side effects or concerns. For comprehensive lifestyle recommendations tailored to breast cancer patients, visit the American Cancer Society’s healthy living after breast cancer page and the Breastcancer.org lifestyle changes guide.

48. Staging and Survivorship Planning

The stage at which breast cancer is diagnosed plays a pivotal role in shaping survivorship planning and long-term follow-up care. Patients with early-stage disease (Stages 0-II) typically focus on monitoring for recurrence, managing side effects of treatment, and maintaining overall health. Follow-up visits may include regular physical exams, mammograms, and discussions about lifestyle, bone health, and emotional well-being. The frequency and intensity of surveillance are often less rigorous than for those with higher-stage diagnoses.

For patients diagnosed with advanced-stage (Stage III or IV) breast cancer, survivorship planning involves more intensive monitoring, ongoing systemic therapy, and management of chronic complications or symptoms related to metastatic disease. Multidisciplinary care is essential, with regular input from oncology, primary care, supportive care specialists, and psychosocial services. Survivorship plans should be personalized, addressing unique risks, cognitive or functional changes, and the need for genetic counseling or fertility support if appropriate.

Regardless of stage, survivorship care plans are valuable tools that outline tailored follow-up schedules, symptom management strategies, and resources for rehabilitation and support. For more on survivorship guidelines, visit the American Cancer Society’s guide to survivorship care plans and the Breastcancer.org survivorship page.

49. Staging and Palliative Care

For individuals diagnosed with advanced-stage breast cancer (Stage III or IV), early involvement of palliative care teams is increasingly recognized as a best practice. Palliative care is a specialized form of medical care focused on providing relief from pain, symptoms, and emotional distress associated with serious illness. Its goal is to enhance quality of life for both patients and their families, regardless of prognosis.

While sometimes misunderstood as end-of-life care, palliative care can be integrated alongside active cancer treatments from the time of diagnosis of advanced disease. Early referral to palliative care helps address complex symptoms such as pain, fatigue, breathlessness, and nausea, as well as psychosocial and spiritual concerns. Palliative specialists work collaboratively with oncology teams to coordinate care, facilitate communication, and support decision-making regarding treatment goals and preferences.

Research shows that early palliative care involvement can improve symptom control, patient satisfaction, and even survival in some cases. For more information on the role and benefits of palliative care in breast cancer, visit the American Cancer Society’s palliative care resource and the National Cancer Institute’s palliative care fact sheet.

50. Future Directions in Breast Cancer Staging

The future of breast cancer staging is poised to be transformed by advances in technology, molecular diagnostics, and artificial intelligence. Emerging techniques such as liquid biopsies, which analyze circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or other biomarkers from a simple blood test, offer the potential for non-invasive detection of cancer spread and early recurrence. These approaches may eventually complement or even replace some traditional imaging and tissue biopsy methods, providing real-time insights into tumor dynamics.

The integration of next-generation sequencing and comprehensive genomic profiling is expected to further personalize staging by revealing the genetic and molecular landscape of each patient’s tumor. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are already being developed to enhance imaging interpretation, predict disease progression, and refine risk stratification based on complex data sets.

Additionally, novel imaging modalities, such as advanced PET tracers and high-resolution MRI, may improve the detection of small or early metastatic lesions. As these technologies evolve, staging will become even more precise, enabling tailored treatment strategies and better outcomes. For more on the future of cancer staging, visit the Nature Reviews Cancer article on the evolution of cancer staging and the National Cancer Institute’s overview of liquid biopsies.

Conclusion

Understanding breast cancer staging is essential for making informed treatment decisions, predicting outcomes, and guiding long-term care. Accurate staging empowers patients and providers to choose the most effective therapies and anticipate future needs. Timely screening—such as regular mammograms and clinical exams—remains a cornerstone of early detection, improving the likelihood of diagnosis at a more treatable stage. Proactive health management, including discussing risk factors, seeking genetic counseling when warranted, and staying informed about the latest advances, can make a significant difference in outcomes. For further guidance on breast cancer prevention and early detection, visit the American Cancer Society’s screening and early detection page.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational purposes only. While we strive to keep the information up-to-date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability with respect to the article or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained in the article for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this article.

Through this article you are able to link to other websites which are not under our control. We have no control over the nature, content, and availability of those sites. The inclusion of any links does not necessarily imply a recommendation or endorse the views expressed within them.

Every effort is made to keep the article up and running smoothly. However, we take no responsibility for, and will not be liable for, the article being temporarily unavailable due to technical issues beyond our control.